The Bookworm: 'All About the Story'

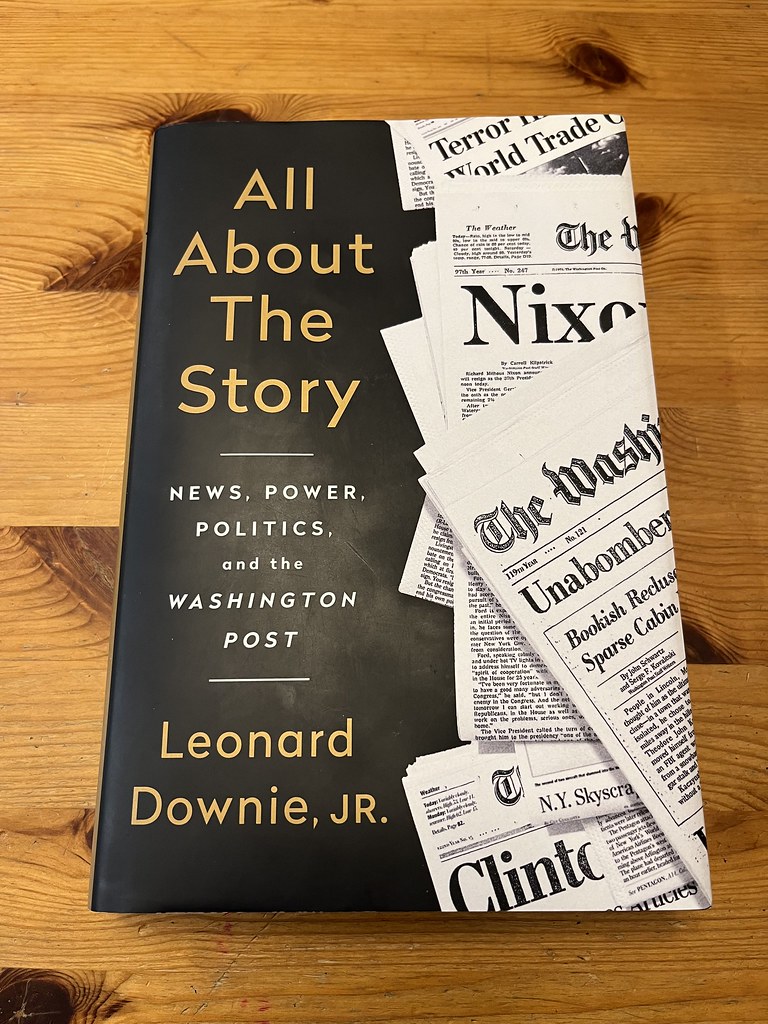

All About the Story: News, Power, Politics, and the Washington Post, by Leonard Downie, Jr. 385 pages. Public Affairs. 2020.

But I believe that the journalist’s role as a singular kind of citizen is to inform other citizens as truthfully and impartially as possible about what they need to know to participate effectively in civic life. Today, especially, with all the accusations of news media bias, it is more important than ever for truth-seeking journalists to avoid all appearances of bias and to let their work speak for itself. It needs to be all about the story. (p. 242)

Two down, three to go.

My dutiful mission to read all the books The Librarian has given me for Christmas before reading Led Zeppelin’s biography continues. Up next was Leonard Downie Jr.’s All About the Story, which I was given in 2020 (better late than never).

All About the Story is an engrossing and informative memoir about Downie’s long career at the Washington Post. Spanning his internship in 1964 that parlayed into a full-time gig, his final days as the Post’s executive editor in 2008, and beyond, Downie recounts all his big breaks, big stories, and the major events he helped cover. He gives readers an inside peek at the inner workings of the Post newsroom, detailing the insane work done to research and get stories right and the tough discussions between reporters, editors, and even the Post’s owners. It is the story behind the stories.

All About the Story was an exciting read for me, an off-and-on journalist since high school. (The journalism bug bit me and its venom will forever course through my veins—though my anxiety about deadlines and talking to people are powerful remedies.) I loved reading about the characters in the newsroom, their quirks and stories. It took me back to my own, though very limited, experience as a newspaper reporter. In many ways, some of the book reminded me of The Paper, especially when he writes:

When the presses started up to print the first pages of the Post’s earliest edition at about 10:30 each evening, the whole building shook. Feeling those tremors when working late in the newsroom was a thrill of which I never tired. (p. 23)

Downie’s experience as a reporter was very different from mine, which was both surprising and refreshing. I always assumed reporters were rushed and overwhelmed by stories every day. Life at the Post, it seemed, was different, especially when Downie became an investigative journalist and was able to do research for days. Working at the Post was obviously an advantage; the bigger the paper, the less work everyone does. Though I do not recall him outlining his daily routine and any deadlines while he worked the crime beat at the beginning of his career, I did not get the sense he was rushed or constantly had a deadline looming, that there were inches he needed to fill for a certain edition of the paper and editors were breathing down his neck. That was advantageous for him, something I envied. Though he mentions having to “overcome my natural shyness to ask questions” (p. 34), Downie is obviously cut out to be a daily newspaper journalist (I am not), so that likely played a factor in his experience as well.

The book is easy to read, concise, and down to earth. It sometimes feels self-important but that is kind of the point of memoirs. There are typos here and there but the copy is as clean as normal.

Downie provides a great inside perspective of the Post’s legendary Watergate coverage. I expected a rehash of the same old stuff, à la All the President’s Men, but it was much more in depth and engaging. It reveals and details the conflicts that arose within the newsroom, especially between the separate metro and national news staffs. (Watergate was and stayed a metro story because it started with a local burglary. As the story grew in scope, the skeptical national editors and writers felt they should take over but were always rebuffed.)

Watergate is just one of the many major events Downie helped cover as either a reporter or editor. Name a nationally significant event between the mid-1960s and 2008 and Downie was somehow involved in its coverage. The book is organized chronologically by them. It’s crazy how much he experienced, and he provides informative and objective overviews of his involvement, what happened, and how the paper covered it.

Those overviews were appreciated for the events in my lifetime, especially those when I was aware of what was happening but too young to understand. His accounts regarding the Unabomber and numerous scandals involving the Clintons were very informative and filled gaps in my knowledge. His accounts of 9/11, the build up to the invasion of Iraq, and the war and messy occupation that followed were uneasy for me to read since it was an emotionally charged era, but they were still informative and appreciated.

The Post’s coverage of the Clintons touches on Downie’s strong commitment to holding the powerful accountable, regardless of political affiliation, the leanings of the editorial page, and readers’ opinion. Downie was dedicated to truth. In a commitment to remain nonpartisan and uninvolved, he stopped voting in 1984 when he became the Post’s managing editor:

As the final decision maker on the Post’s news coverage, I did not want to decide, even privately, who should be president or hold any other public office, or what position to take on policy issues. I wanted my mind to remain open to all sides and possibilities. (p. 241)

I admire that a lot. In that sense, All About the Story is the testament of a model journalist.

Comments

Post a Comment